The Road to 270: Washington, D.C.

By Seth Moskowitz

November 18, 2019

Editor's Note: 50 Mondays after today is November 2, 2020, the day before the presidential election. That gives us 50 weeks to review the 50 states.

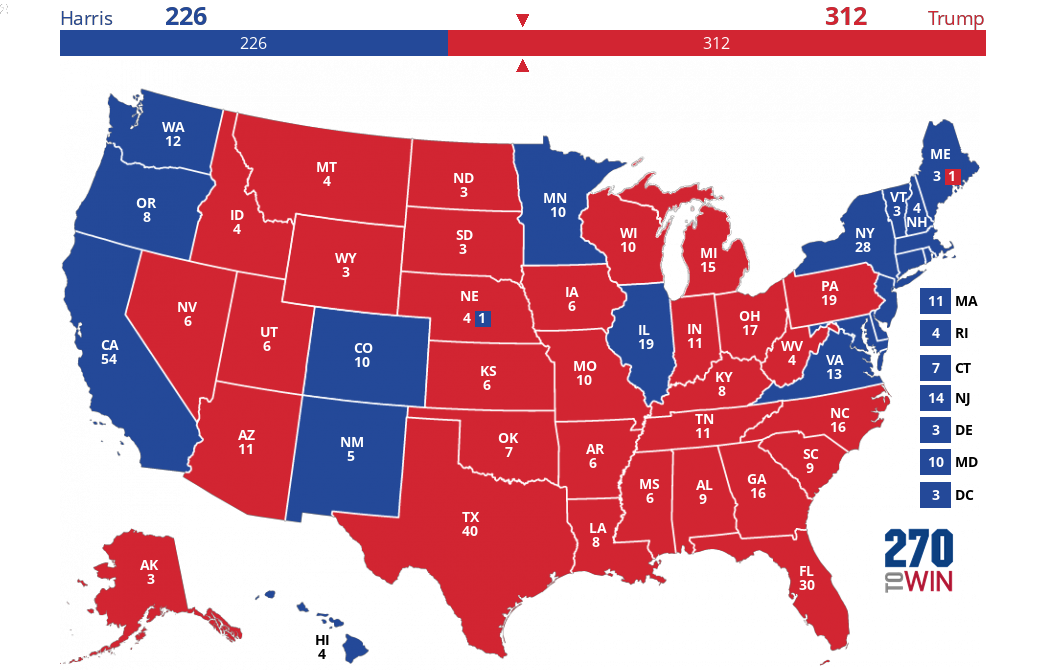

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears. Leading off is Washington, D.C., the only non-state entity that casts electoral college votes in the United States presidential election.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. You can reach Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Washington, D.C

The quadrennial contest for Washington, D.C.’s three Electoral College votes is consistently the least competitive in the nation. The District's residents began casting votes for president in 1964 and no Republican nominee has ever won an electoral vote. In 2016, Hillary Clinton received nearly 23 votes for each one cast for Donald Trump, winning by a 91% to 4% margin.

Before getting to the District’s outlook for 2020, let’s look at its history as our nation’s capital and why it has electoral votes at all.

Constitutional Cliff Notes

The Constitution stipulates in Article I, Section 8 that the U.S. Congress has the power to choose the seat of the Federal Government. It specifies that the District cannot exceed ten square miles and that Congress shall “exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such District”. The Framers gave Congress this exclusive power over the District and separated it from the states so that no one state would have untoward influence over Congress. This independence also meant that the Federal Government would not have to rely on the states for physical protection.

Following ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788, New York and Philadelphia served as the temporary seats of government. In 1790, Congress decided that the future capital would be along the Potomac River. This was a part of the secretive Compromise of 1790 involving Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson. Madison and Jefferson agreed to allow the Federal Government to assume states’ debts while Hamilton agreed to establish a southern capital.

The president, George Washington, was given the power to decide the exact location of the capital. He settled on a tract of land between Maryland and Virginia. This federal territory was named the District of Columbia after Christopher Columbus. The city inside, Washington, was meant to honor the first president and man who chose the permanent capital’s location. In 1800, Congress officially moved to Washington, D.C.

The people living in the new seat of government, however, were no longer residents of a state. And because the Constitution only delegated electoral votes and congressional seats to the states, Washington, D.C. residents lacked federal representation.

This lasted until ratification of the 23rd Amendment in 1961. The Constitution grants each state electoral votes equal to its total representation in Congress (senators plus representatives). The new amendment gave Washington, D.C. a number of electors “equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives in Congress to which the District would be entitled if it were a State, but in no event more than the least populous State”. In practice, this limits Washington, D.C. to three electors because seven states, including the least populous state of Wyoming, have just three. However, it is also the number of electoral votes it would have as a state based on its current population.

At the time, the Amendment’s ratification was not crushed by political partisanship, as would likely be the case today. The primary political wedge endangering ratification was race rather than partisanship. According to the U.S. Census, the District was 54% black in 1960. Only one former Confederate state, Tennessee, voted to ratify the Amendment even though Democrats controlled most of the Confederate state capitals. Likewise, Republican-controlled northern states did vote to ratify. By 1970, the District had become 71% black, increasing 17% in just 10 years. This demographic change along with the 1964 Civil Rights Act made ballot access easier for black and minority residents. It shifted the District safely into Democratic hands.

The Ongoing Push for Statehood

Today, though, any structural reform that would tilt the electoral landscape is unlikely. Statehood, or any legislation that gives Washington, D.C. full representation in Congress, would essentially guarantee Democrats two additional Senators. It would also give residents a Democratic voting member in the U.S. House^. Even back in 1978, by which time the Democratic Party’s advantage in Washington, D.C. had become clear, a proposed Constitutional Amendment giving the District full Congressional representation failed. Although the amendment passed Congress with the requisite two-thirds support in both chambers (the last time any proposed amendment has done so), only 16 states voted to ratify it. This was far short of the 38 states needed.

The partisanship that defeated the amendment back in 1978 has only strengthened. The Republican Party’s 2016 Platform calls for “Preserving the District of Columbia” while Congressional Democrats in both the House and Senate have introduced bills that would create the State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth. Two hundred and twenty-three Democrats* have sponsored the House Bill and 36 Democrats have sponsored the Senate version. No Republicans have signed on to either.

Washington, D.C.’s Electoral History and Demographics

In every presidential election since the 23rd Amendment, Washington, D.C. has voted overwhelmingly for the Democratic Party. This was the case even in 1972 and 1984, when GOP incumbents (Nixon and Reagan) had landslide 49-state wins.

Both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton continued the legacy of Democratic domination in the capital. In 2012, Obama beat Mitt Romney 91% to 7%, an 84% margin. In 2016, Clinton beat Donald Trump 91% to 4%, an 87% margin. By comparison, the most Democratic state in both those elections - Hawaii - went to Obama by a 43% margin in 2012 and Clinton by 32% in 2016.

Today, the District is approximately 48% black, a reliably Democratic voting bloc. In comparison, non-college educated whites, a key Republican constituency, only make up about 2% of the population. The District as a whole is densely urban and continues to grow quickly. These demographic trends make it clear why it is Democrats’ deepest blue stronghold.

And the Capital’s political effects are not contained within its boundaries. D.C.’s expanding suburbs helped Democrats flip Virginia's 10th congressional district in 2018 and partially explain why Virginia is becoming a reliably blue state in presidential elections.

Come next November, the Democratic nominee is all but certain to win Washington, D.C.’s three Electoral College votes. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a world - at least in the foreseeable future - where a Republican wins the nation’s capital.

^ Whether this would be a net gain for Democrats is unknowable. The number of voting seats in the U.S. House is fixed by law at 435. Assuming no change in the law, one state would lose a congressional seat.

*Excluding the primary sponsor, Washington, D.C.‘s non-voting delegate.

Next Week: Wyoming