The Road to 270: Idaho

By Seth Moskowitz

January 13, 2020

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Idaho

Pre-Statehood

Through the Revolutionary War and American Independence, much of North America was still unexplored by Europeans or their descendants. This included the territory that would eventually become Idaho. Lewis and Clark first explored the region in 1805 which was, at the time, home to about 8,000 Native Americans.

Quickly following the expedition, settlers began arriving in the region. Missionaries, farmers, fur traders, and miners traveled along the Oregon Trail and many settled in the territory that would later become Idaho. Ownership of the land was initially disputed, as it was claimed by both Britain and the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 brought the dispute to an end. Two years later, the United States established the Oregon Territory, which comprised today’s Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and eastern portions of Montana and Wyoming.

In 1853, the Washington Territory took over all of the Oregon Territory except for the region we now know as Oregon. With the discovery of gold, and later the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, the population of the region grew and in 1863 the United States established the Idaho Territory. It originally comprised modern day Idaho as well as nearly all of Montana and Wyoming. Soon, the territory shed most of the future Montana and Wyoming, and by 1868 Idaho had the boundaries of the modern state.

The territory was divided between the north and south. The north was composed mostly of settlers who had come to the territory as miners and loggers. Meanwhile, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as Mormons) settled the southern and eastern portion of the state. Many of these Mormons had migrated from Utah.

Over time, the north became anti-Mormon, a divide that continued to grow through the 1880s. The antipathy led to the passage of the Idaho Test Oath Act in 1884. The Act was meant to deny Mormons, who made up about a quarter of the electorate and voted overwhelmingly Democratic, the right to vote.

After the restrictions were implemented, the territory became staunchly Republican. Intent on adding a Republican leaning state to the Union, national Republicans began to push for statehood in 1888. Two years later, in 1890, Congress and Benjamin Harrison admitted Idaho as the 43rd state.

The anti-Mormonism of the 1880s was nothing new for the Republican Party. In 1856, the National Republican Platform named polygamy and slavery the “twin relics of barbarism.” Polygamy was a relatively common practice among Mormons, and the platform, as well as the aforementioned Act, were clear messages opposing this lifestyle.

The Act was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1890. Following that, the leader of the Church encouraged his followers to acquiesce to civil laws regarding marriage. The state legislature responded by repealing the anti-Mormon voting restrictions in 1893. From then on, Mormons in Idaho were free to vote and hold elected office.

Presidential Election History

These new voters, and a populist groundswell, upset the Republican Party’s expectation that Idaho would lean Republican from the beginning. In fact, it wasn’t until the state’s fourth election in 1904 that Idaho would vote Republican on the presidential level. The first three elections show the state’s populist roots and the power of the newly enfranchised Mormon population.

At the time of the 1892 presidential election, Idaho was still divided between Republicans in the north and anti-Republican Mormons in the south. Voting laws would be in place for another year, greatly restricting Mormons’ right to vote in the south. But a populist sentiment had been growing among the silver miners and farmers who supported moving away from the gold standard. The Republican nominee, Benjamin Harrison, supported the gold standard. The Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland, didn’t run in Idaho, allowing support to coalesce around the Populist Party’s candidate James Weaver. Weaver beat Harrison by 10% in Idaho, validating Cleveland's decision not to run in the state.

Idaho followed a similar trend in the next two elections of 1896 and 1900. In these elections Idaho’s populist and Mormon voters together gave the populist Democrat, William Jennings Bryan1, resounding victories in the state. In 1896, Bryan beat William McKinley by 57% in Idaho even as he lost the national popular vote by 3%. Four years later, McKinley was coasting to a second term on a strong economy and victory in the Spanish-American War. The incumbent also had the progressive, energetic, and popular Theodore Roosevelt as a running mate. Nevertheless, Bryan won Idaho again, though with a smaller margin of 4%.

Four years later, in 1904, Republicans finally carried Idaho. Theodore Roosevelt ran as a progressive Republican and won Idaho with a 40% margin. While the state would vote for Democrats in future elections, they were generally either landslide elections or unique circumstances.

The only Democratic presidential nominee to win Idaho between 1904 and 1928 was Woodrow Wilson. Wilson won the state in 1912 due to Theodore Roosevelt splitting the Republican vote and again in 1916 when he ran on keeping the United States out of World War I. Otherwise, Idaho, along with most northern states, voted regularly for the Republican nominee. The state’s progressive and independent streak was also present throughout the first quarter of the century, as socialist candidates received 7%, 11% and 6% in 1908, 1912, and 1916. The Progressive Party candidate Robert La Follette received 37% of Idaho votes in 1924, outpacing the Democratic nominee by over 20%.

In 1932, with the realigning election of Franklin Roosevelt, Idaho swung back to the Democratic Party. This was also the first election since statehood in which Idaho elected a Democratic Representative to the House. As with other farming states, Idaho had suffered during the Great Depression. The average Idahoan’s income dropped 49% between 1929 and 1932, placing it behind just six other states in that grim ranking. FDR’s New Deal appealed to the struggling population and won him a blanket victory in the Mountain West states. These western and northern farming states generally received the most in New Deal expenditures per capita during the 1930s.

While Idaho continued to vote Democratic on the presidential level through 1948, by 1940 the state’s rightward trend is apparent. The Democratic margins between each election from 1936 to 1948 were 30%, 9%, 3.5%, and 2.7%. In 1952, the moderate Eisenhower carried Idaho by 31%. From this election on, Idaho would vote for the Republican nominee with one exception in the Democratic landslide of 1964. Since then, no Democratic nominee has received more than 37% of the popular vote in the state.

However, beginning in the 1930s and lasting through the 1970s, Idahoans were willing to split their tickets. With the exception of 1951 – 1956, Idaho had at least one Democratic U.S. Senator from 1933 through 1980. Similarly, Idaho elected several Democratic House members through much of the mid-century.

As the parties began to sort along religious lines in the 1970s, Democrats started losing their downballot power in Idaho. Mormons, put off by the Democratic Party’s embrace of socially liberal policies like abortion and gay rights, steadily shifted towards the Republican Party. The decline of the union heavy mining and timber industries also undercut Democratic power and organizing strength in the state. And while Democrats did have a brief period of electoral success from 1988 to 1990, this died off quickly and voters quickly fell back in line as Republicans.

As the parties continued to sort ideologically, racially, and demographically, Idaho moved further right. Following the 1992 midterms, only one Democrat — in a 2008 House race — would win a federal election in Idaho.

A State in-Flux

Over the past 30 years, Idaho’s population has nearly doubled, growing from 1 million to 1.8 million. In 2019, Idaho was the fastest growing state in the nation by percentage. It grew by 2.1%, outpacing the runner up, Nevada, by 0.4%. People are moving to Idaho for jobs in the booming tech industry, an affordable cost of living, and the state’s natural beauty.

The population boom originally worried conservatives. They believed that people moving in from neighboring states including California, Washington, and Oregon would bring west coast liberalism with them. This didn’t ensue, as many of the new Idahoans were leaving their homes for cultural reasons and fit nicely into the more libertarian ethos of Idaho’s Republican Party.

While the growth hasn’t transformed Idaho’s politics, it has changed the character of the state. The potato-farming, religious, rural Idaho has become a center for innovation and startups. The state ranks high among various indicators of entrepreneurship and has one of the highest number of patents per capita in the country. The industry leaders in Idaho — Micron, Hewlett-Packard, Simplot — have helped built a techy, entrepreneurial ecosystem in the capital city, Boise.

Unlike the Silicon Valley in California, Boise is not a liberal bastion. The entrepreneurs and startups were drawn to the state's less restrictive regulatory environment and low taxes, and generally support the Republican Party’s mission to that end.

Current Political Landscape

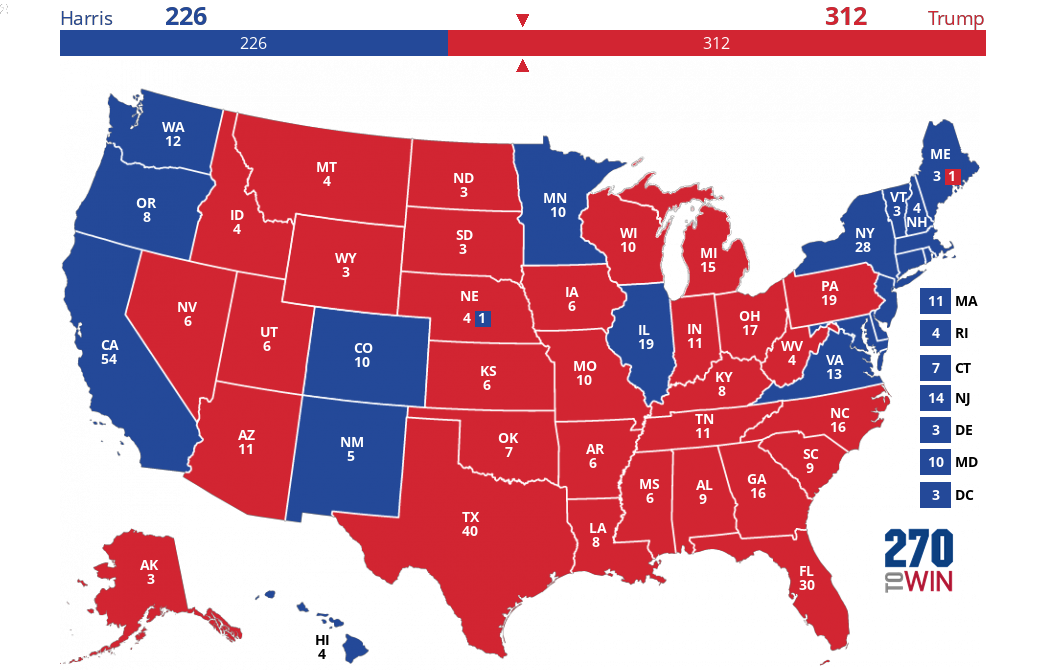

Since the turn of the century, no presidential Democratic candidate has come within 25% of winning Idaho and its four Electoral College votes. The GOP nominee won in 2008 by 25%, in 2012 by 32%, and in 2016 by 32%.

Donald Trump received 5% less of the vote in Idaho than Mitt Romney did in 2012. Most of this vote went to Evan McMullin, the third-party candidate who won 7% of the state. McMullin, who is Mormon himself, had the greatest appeal among Idaho’s Mormon voters who are clustered in the southeast. McMullin outran Hillary Clinton in a total of seven counties, all of which are in this region of the state. Of these counties, he ran strongest in Madison County, winning 30% of the vote to Trump’s 57% and Clinton’s 8%.

This ongoing Republican dominance is in line with national trends. Idaho's population is 63% non-college white, the core of the Republican base. It’s also the 7th least densely populated state, with an average of just 22 people per square mile.

The state is also 40% Evangelical Protestant or Mormon. The Idaho Republican Party reflects this religious bent, with the preamble to the party’s platform beginning “We are Republicans because we believe the strength of our nation lies with our faith and reliance on God our Creator.” The socially conservative streak continues through the platform, which pushes legislators to “protect the traditional family”, opposes abortion, supports the death penalty, and encourages “swift and just punishment for the lawbreaker”. This Republican Party has a lock on the state legislature, holding ¾ of both chambers.

From statehood through the 1960s Idaho was politically competitive. In the current era of partisanship, however, Idaho has moved steadily into the GOP camp. This trend looks likely to continue in November, making Idaho a safely Republican state from the presidential election down to the Statehouse.

1 No person has ever won more electoral votes without becoming president than William Jennings Bryan. He amassed 493 across three elections (1896, 1900 and 1908).

Next Week: Vermont