The Road to 270: Tennessee

By Seth Moskowitz

March 2, 2020

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Tennessee

Tennessee has a history of distinguishing itself from its southern neighbors. It resisted secession and the Civil War, was first to break the "Solid South" electoral block, and was home to the first southern city to desegregate. This independent streak goes back to Tennessee's earliest days before it was a state.

Statehood and Early Presidential Politics

The territory that would become Tennessee was originally part of North Carolina. In 1789, after years of dissatisfaction with North Carolina governance and previous secession attempts, the region broke off to form the “Territory South of the Ohio River”. Tennessee was admitted to the Union seven years later, in 1796.

Like most of the agrarian south, Tennessee reliably cast electoral votes for Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party. It did so in each of its first eight elections from 1796 to 1824. The last of these, 1824, featured the Tennessean general Andrew Jackson. Jackson won his home state with 97% of the popular vote and won the plurality of the national popular vote with 41%. He lost that election due to a “Corrupt Bargain” between John Quincy Adams and Speaker of the House Henry Clay.

Four years later, the Tennessean populist ran again under his new Democratic Party — the same one we have today — and dominated his home state, the national popular vote, and the Electoral College. During his tenure, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act that forcibly displaced Native Americans out of the Southeastern United States, including Tennessee. The Trail of Tears, as it would come to be known, did little to hurt Jackson’s electoral fortunes. He won the popular vote and his home state in a landslide.

Unlike its southern neighbors, however, Tennessee broke from the Democratic Party for the next five elections. From 1836 to 1852 Tennessee would vote for the Whig Party, which built an effective infrastructure and tailored message in the state. As historian Jonathan Atkins writes,

"The Tennessee Whig Party built its platform on warnings that powerful, demagogic forces conspired to rob republican citizens of the liberty won during the American Revolution. Whigs also argued that the power of government should be used to promote the public good. This tactic proved especially successful during the economic depression of the late 1830s and early 1840s, when Whig supporters recognized that the party's success could enhance their material well-being."

Slavery and Civil War

By 1856, however, the question of slavery and the survival of the Union overshadowed all other political concerns. In 1856, Tennessee voted for Democrat James Buchanan, and in 1860 for Constitutional Unionist, John Bell. The Constitutional Union Party was formed to hold the Union together and performed best among the states forming the border between North and South. The only three states to vote for it — Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky — were largely pro-slavery, but wanted to hold the Union together. They had reason to fear that a civil war would be fought within their borders.

Displaying its moderate tendencies, Tennessee initially voted against secession. Later, following the attack on Fort Sumter, the state changed tack and joined the Confederacy. The state’s population, however, was not uniform in its support for secession. The eastern third of the state, made up mostly of homesteads and family farms, favored staying in the Union. The rest of the state, covered with large cotton and tobacco plantations, relied on slavery and supported secession.

Tennessee and the Solid South

After the war, Tennessee’s voting patterns reflected these feelings on secession and slavery: whites in the east voted Republican and those in the center and west supported Democrats. In the first post-war election of 1868, Tennessee voted Republican. Many newly freed slaves were able to vote for the first time while some whites were disenfranchised during Reconstruction. As whites regained the franchise and African Americans faced exclusion and voter suppression, Tennessee shifted into the reliably Democratic column. From 1872 through 1916, the state would vote exclusively Democratic. Unlike other southern states, and in particular those in the Deep South, Tennessee regularly gave Republicans over 40% of the popular vote.

This moderation would help make Tennessee the first state to break the “Solid South”, the group of southern states that had voted uniformly Democratic since 1880. In 1920, due to the unpopularity of Woodrow Wilson’s foreign entanglements in the isolationist Appalachian regions of Tennessee, Republican Warren Harding would overcome his party’s drought in the state. Again in 1928, largely due to an anti-Catholic sentiment haunting Democratic candidate Al Smith, Republican Herbert Hoover would again break the Solid South and carry Tennessee by 8%.

With the popularity of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal, Tennessee again shifted back to Democrats. The Tennessee Valley Authority, a state-owned enterprise created as a part of the New Deal helped employ, power, and pull a suffering region out of the depths of the Depression. Though not without its share of controversy and resentment, the TVA and Roosevelt’s legacy helped solidify Tennessee as a Democratic state.

Shifting Rightward

After Roosevelt’s landslide in 1936, however, Tennessee began shifting rightward every election cycle. The trend finally overtook Democrats in 1952, when the moderate Republican Dwight Eisenhower beat out Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson by 0.28%. Eisenhower’s victory marks a breaking point in Tennessee presidential politics; after his 1952 victory, no non-southern Democrat would win the state. Republicans would go on to win every election in Tennessee outside of 1964, 1976, 1992, and 1996, when Texan Lyndon Johnson, Georgian Jimmy Carter, and Arkansan Bill Clinton would be the Democratic standard-bearers.

A century after the Civil War, Tennessee’s ancestral voting patterns prevailed. The eastern third of the state remained staunchly Republican while the rest of the state would swing between elections. The once secessionist central and western regions would still sometimes vote for liberal Democrats including George McGovern and Michael Dukakis. Once again, Tennessee’s course is different than those of than its southern neighbors. Most southern states stuck to their Democratic roots until 1964 when the Civil Rights Act fractured the Democratic Party.

As the parties further polarized along social issues including civil rights, abortion rights, gun control, and especially the environment, Tennesseans cut these ancestral ties. In 2000, Al Gore, a former Tennessee Senator and Representative, ran as an environmentalist. The platform played poorly in his home state, which Gore lost by 4%. That year, Gore won 21 fewer counties than Clinton had in 1996. Each subsequent election would see Republicans expand their margin of victory and flip more counties.

Economic Development in the Last Century

Tennessee’s economy, though once reliant on farming and agriculture, has shifted away from its agrarian roots. During the mid-20th Century, the Tennessee Valley Authority and World War Two had drawn manufacturing investment and a labor force into Tennessee. The cheap labor drew in more manufacturing jobs including in the textile and chemical industries. The state continued to attract new industries through the 1970s with its skilled labor force, low taxes, loose regulations, and tight restrictions on labor unions.

In 1983, Nissan opened a manufacturing plant in Tennessee, kicking off a new era in the state’s economy. Other automobile companies, most importantly General Motors, also opened manufacturing centers that helped fuel the state’s economy and built up a skilled workforce that spread to other industries. A vestige of the TVA, Tennessee still produces a significant amount of energy though oil, natural gas, coal, hydroelectric, and nuclear facilities.

The state's economy also relies on transportation and logistics, an industry boosted by the state’s position between the South and the Midwest and Northeast. The tourism industry is healthy, with music lovers drawn to Nashville’s country scene and Elvis Presley’s Graceland Mansion in Memphis. Chattanooga in the southeast has become an unlikely tech hub and the state is still covered in farmland, much of which is dedicated to soybeans, hay, and corn.

Recent Elections and Political Landscape

Downballot state elections lagged behind Tennessee’s national trends. As recently as 2004, Democrats held a government trifecta — holding the Governorship and both chambers of the state legislature. The State Senate was the first to flip in 2005, next was the State House in 2010 and last was the Governorship in 2011. In just 7 years, Democrats lost and Republicans picked up a state trifecta in Tennessee.

Meanwhile, Republicans continued to expand presidential margins in Tennessee. George W. Bush won by 14% in 2004, John McCain by 15% in 2008, and Mitt Romney by 20% in 2012. Republicans gained ground in the rural and suburban communities in the central and western portions of the state. Democrats saw improvements in the most dense and diverse Shelby and Davidson Counties that house Memphis and Nashville.

In 2016, Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton with a 26% margin, the largest since Richard Nixon’s 49-state landslide in 1972. Trump improved on Romney’s margins in 91 of the state’s 95 counties. Clinton would only carry three counties — Shelby (Memphis), Davidson (Nashville), and Haywood, which along with Shelby, is one of Tennessee’s two majority-black counties.

This November, Tennessee will hold elections for president, U.S. Senate and nine U.S. House seats. None of these elections is expected to be competitive.

There is, however, a competitive election happening in the state this week. Tomorrow, on Super Tuesday, Tennessee Democrats will have their say in the party’s primary. There has been a dearth of polling in the state, but if regional and demographic trends are indicative, Joe Biden’s recent success in South Carolina could portend a plurality victory for him here. The Democratic electorate is whiter here than in South Carolina, however, a distinction that is likely to help Bernie Sanders.

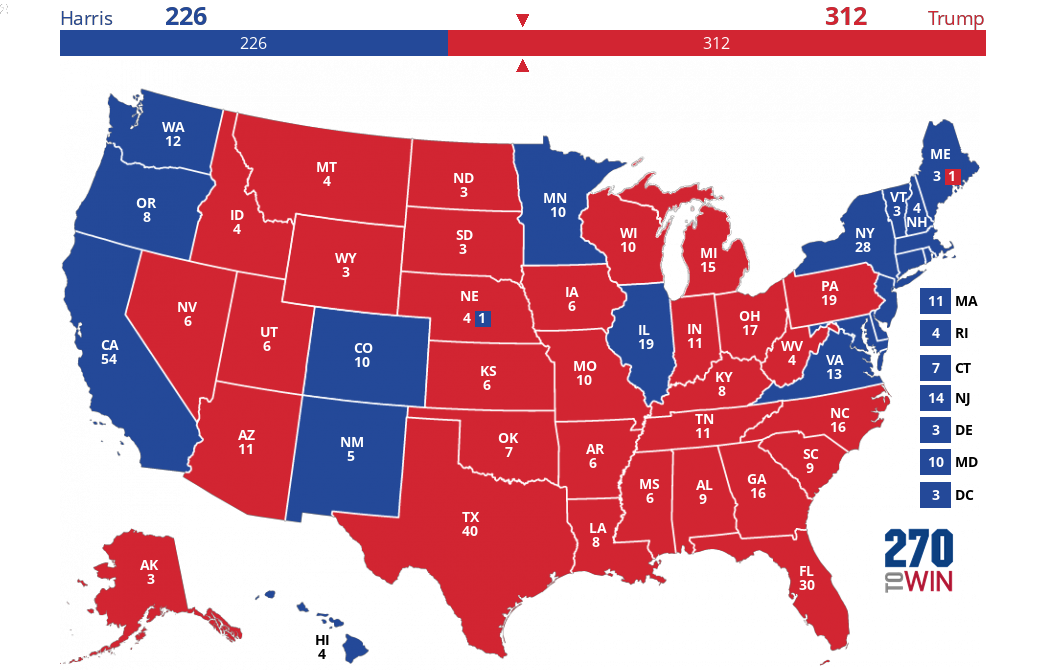

While Tennessee’s primary election results are uncertain, those of the general election are not. It is safe to assume a Trump victory in Tennessee this November, likely with a margin approaching 30%.

Next Week: Maryland