The Road to 270: Rhode Island

By Seth Moskowitz

March 30, 2020

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island

Rhode Island was more competitive in the 2016 than it has been since 1988. Given that Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by 16%, this means little for its top-line electoral fortunes in November. It could, however, indicate a future where Republicans can credibly compete.

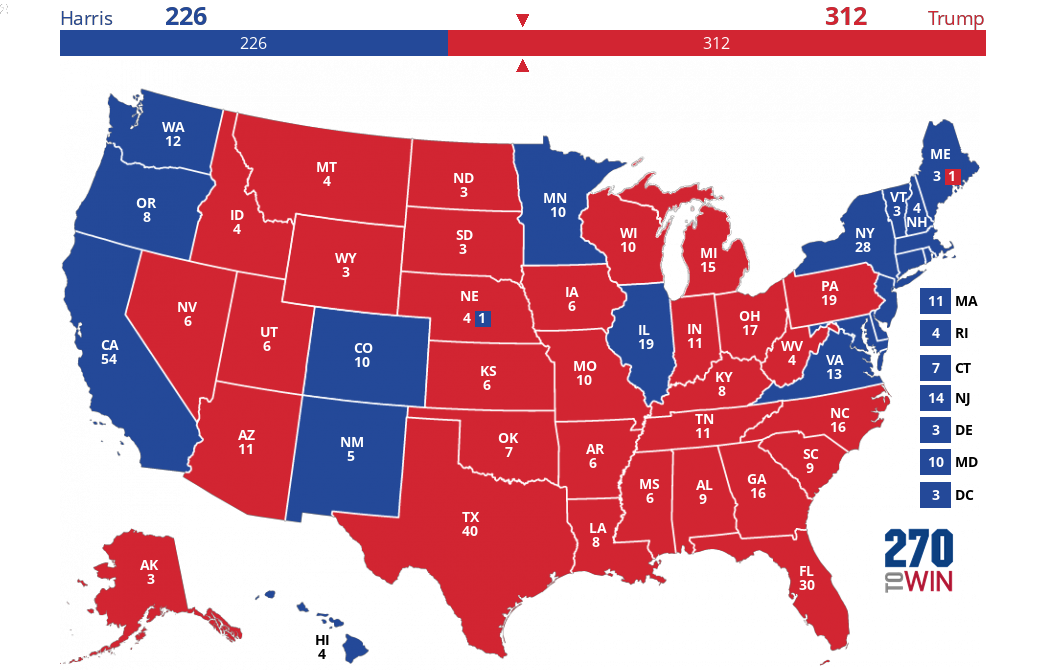

The tiny state — it’s the smallest of them all — packs enough people in to give it four Electoral College votes rather than the minimum of three (although it might not be so lucky following the upcoming Census). Most of the population lives in the coastal and urban areas which favored Clinton while inland ones voted for Trump. In this way, the state looks like the country: its coastal and urban communities are Democratic and its inland ones are Republican. Before we get too deep into the state’s current political and demographic condition, we’ll look back before it was a state.

Becoming A State

Providence Plantations, the first European settlement in the territory that would become Rhode Island, was established in 1636 as a haven for non-traditional religious views. The Founders of the U.S. Constitution would later be inspired by one of the settlement’s ideals in particular — the separation of church and state.

Other settlements quickly followed and in 1644, they united and formed the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The colony’s economy relied on the slave trade — selling rum in exchange for slaves and molasses (with which to make more rum). Fed up with British control and taxation, Rhode Islanders attacked and burned a British ship off their shore. The event, known as the Gaspee Affair, was one of the first examples of violent resistance and edged the colonies closer to revolution.

The first of the 13 colonies to declare independence and the last to ratify The Constitution, Rhode Islanders had an independent streak. They preferred the decentralized Articles of Confederation and only approved the new constitution after promises of a Bill of Rights.

After the American Revolution came the Industrial Revolution and Rhode Island was again at the forefront of change. The state’s first textile machine came in 1787 and its first mill established in 1790. Rhode Island would become home to textile, machine parts, and jewelry industries. Immigrants and Rhode Islanders in search of jobs moved to urban areas, particularly those around Pawtucket (where the first textile mills were established) and Providence.

These workers, though, were excluded from state politics through the mid 1800s. Residents without property couldn’t vote and rural regions had outsized representation in the state legislature. In an attempt to take back power from the Yankee rural elite, Thomas Dorr established a populist party in 1841 with which he created a new government with a new constitution. The existing government quickly ended what is known as The Dorr Rebellion but, in a win for the urban working class, began allowing the landless, native-born, population to vote.

Civil War, Economic Boom, Shift to Democrats

During the Civil War, Rhode Island fought with Lincoln and the rest of the north. In fact, the state was one of the first to abolish segregation in public schools, an act taken in 1866. Rhode Island would vote, along with its northern neighbors, reliably Republican though the 19th Century.

After the war, Rhode Island’s economic and demographic trends continued. Industrial jobs dominated the economy and workers packed into cities to get those jobs. In the cities of Pawtucket, Providence, Central Falls, and Woonsocket, manufacturing and whaling reigned. Newport, in the state's south, was reserved for the wealthy. Summer beach homes and mansions filled the wealthy enclave, distinguishing it from the working-class character in the state’s north.

All through this booming economy, Rhode Island would vote Republican. It did so in every election from 1856 through 1924 except one year, 1912, when Republicans split their vote between William Taft and Theodore Roosevelt.

As the economy began to stumble in the 1920s, Republicans lost their grip on the state. Due in part to the popularity of a synthetic silk called Rayon, the textile industry took a hit in the 1920s and Rhode Islanders lost jobs. Democrats also organized growing urban, Catholic, immigrant, and labor communities into a voting coalition that, along with economic frustration, tipped the state to Democrat Alfred Smith in 1928. With the advent of Great Depression and Franklin Roosevelt’s popular New Deal, Rhode Island shifted further into the Democratic camp — a transition that would never be reversed. From 1928 through 2016, the only Republicans to win the state would be the moderate Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956 and Richard Nixon and Ronald Regan in their landslides of 1972 and 1984.

World War II to 2020

World War II changed the state’s economy. As textile mills went out of business, the state manufacturing capacity shifted towards ship and submarine building. The Navy became the state’s largest employer and the defense industry continued to build up around it.

Demographic change accompanied the economic one. After the war, soldiers and urbanites left the cities — with their cramped living conditions, bad schools and unsafe streets — for the more comfortable suburbs. Providence lost nearly 70,000 residents between 1950 and 1970. Meanwhile, Cranston and Warwick, outside the city, nearly doubled in size. Natural and man-made disasters — including hurricanes in 1954, 1955, 1985, and 1991 and oil spills in 1989 and 1996 — disrupted urban renewal development meant to draw Rhode Islanders back into the cities. Providence’s population peaked in 1940 at 254,000 and bottomed out in 1980 at 157,000.

During this period, immigration to Rhode Island continued. Even as the cities were shrinking from 1950 to 1980, the state grew by over 150,000. Immigrants were simply moving into the suburbs and then the “outer suburban rings” and rural towns, including Charlestown, Glocester, Narragansett, Scituate, and West Greenwich.

The defense industry took more hits in the 1970s when the Navy decided to relocate its destroyer fleet out of Newport and deactivate the Naval Air Station at Quonset Point. While Newport still has a naval station and defense manufacturing continued for another two decades, the drawdown and end of the Cold War all but ended manufacturing as the state’s economic backbone.

In its place came the service industries of tourism, education, finance, and business. Tourists came for the state’s history, beaches, environment and natural charm. Students and educators came for the Providence-based Ivy League, Brown University. Businesses including Citizens Bank and CVS Pharmacy moved their headquarters to the state in the 1990s. While manufacturing is continuing to shrink, the state still produces submarines, ships, jewelry, and silverware.

Today, Rhode Island ranks 13th in portion of the population with a Bachelor’s Degree and 18th for median household income. These stats are less impressive when compared to Rhode Island’s rich and educated New England neighbor states. The state also has a high cost of living, tight business regulations, notoriously deficient infrastructure, and sluggish GDP growth, low factory wages, public corruption, and a large budget deficit. Most of these problems have plagued the state for decades and continue today.

Democratic Dominance and a Turn to Trump

Rhode Island has voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1988, doing so with double digit margins each year. No Republican would win a single of the state’s five counties from 1988 until Donald Trump managed to flip one in 2016.

At the turn of the Century, Rhode Island was clearly Democratic but not geographically divided like it is today. In 2000, Al Gore beat George Bush by 29%. That year, there was not a clear geographic split that determined if a town or congressional district voted more heavily Democratic or Republican than another. Communities across the state voted for Gore.

Compare that to the 2016 election in which Hillary Clinton carried the state by a smaller 16%. This time, the election featured a clear geographic divide — communities on the coast and in metro areas supported Hillary Clinton while those inland voted for Trump. The reason behind this geographic split, however, lies in demographics.

The state is about 72% white, 16% Hispanic, 8%, black, and 4% Asian. The demographic group that has shifted most toward the GOP in recent years is non-college educated white voters. This population makes up 51% of the state.

If we look at the town in which Trump received the highest percentage of the vote — Scituate, which is located in the center of the state — we see that, relative to the state as a whole, it is far whiter (96% to 72%), less educated (33% to 40%) , and less wealthy ($63,000 to $93,000 median household income) than the state as a whole. While Al Gore received only 6 votes fewer (less than .01% of the vote) than Bush in 2000, Donald Trump clobbered Clinton by 25% in 2016.

If we now look to Clinton’s best city — Providence — we see that, compared to the state, it is far more diverse (43% Hispanic and 16% black) than the state overall. While, in 2000, Al Gore received 74% of the vote, Clinton managed 81% in 2016. A similar trend can be seen in the wealthy enclaves and beach towns along coast.

These two examples illustrate the dominant trends in Rhode Island. First, the white working-class voters who populate the state’s inland communities are shifting rightward. Second, the more diverse communities, as well as the rich, educated coastal ones, are sticking with, or moving towards, Democrats.

Even with these internal changes, however, the state as a whole looks safe for Democrats. While it will be instructive to see if Donald Trump’s populist message is again able to appeal to slices of the state, the big picture is clear: Rhode Island will be blue in November.

Next Week: Utah