The Road to 270: North Dakota

By Seth Moskowitz

December 30, 2019

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

North Dakota

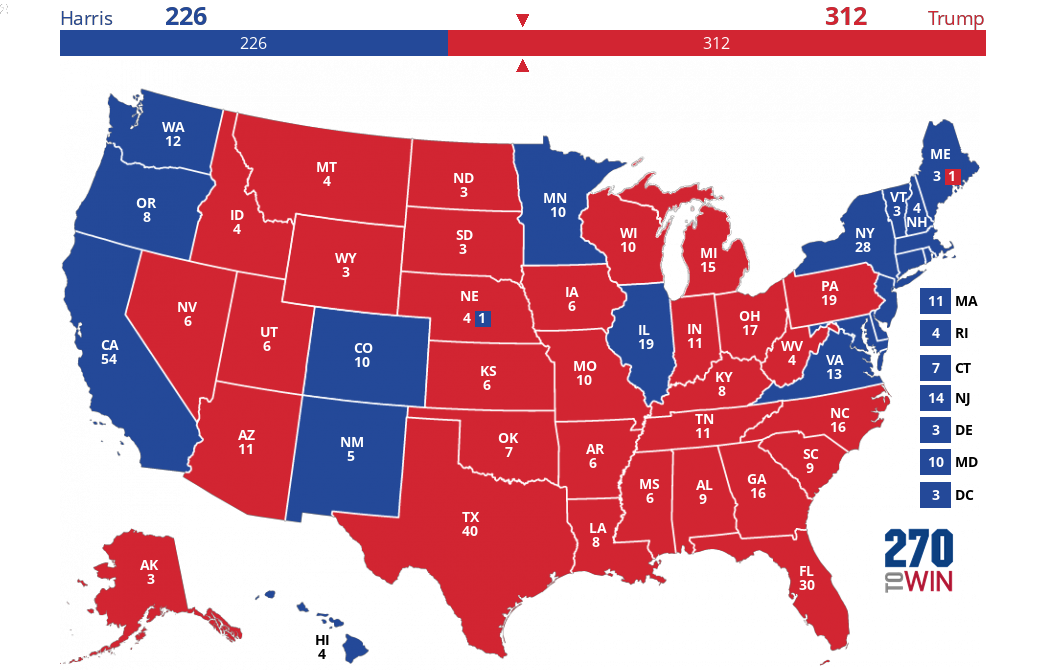

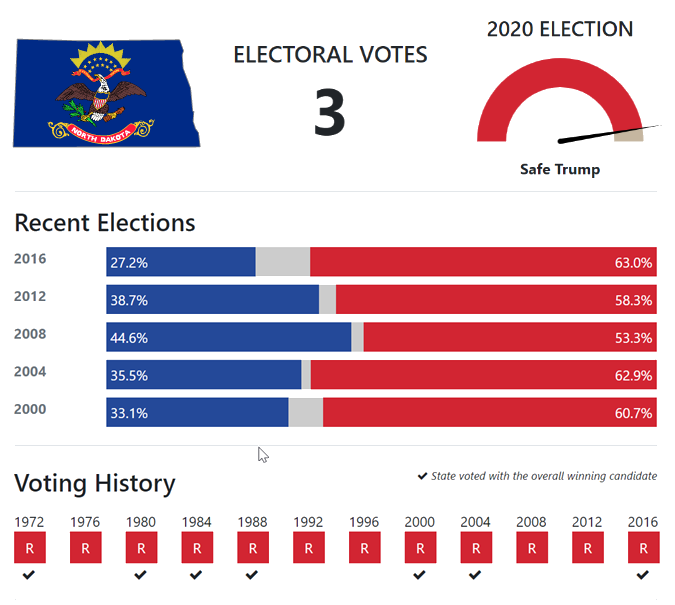

In 2016, Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton in North Dakota by 36%, greatly expanding upon Mitt Romney’s 20% margin of victory from four years earlier. This 16-point jump is the greatest rightward shift made by any state between 2012 and 2016. To understand how North Dakota, a state with origins in left-wing populism, would become one of the most conservative in the span of 100 years, let’s look back to its origins.

Statehood, Farming, and a Population Boom

Congress originally organized the Dakota Territory in 1861. It was primarily composed of land acquired from France in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. During the early and mid 1800s, the U.S. traded with, repressed, and eventually drove drove out Native Americans in the territory. In 1870, when the population of northern Dakota was just 2,400, farmers and homesteaders began to move into the territory. By 1880 northern Dakota had 37,000 residents. In 1890, the year after statehood, North Dakota’s population had grown fivefold to 191,000.

Both North and South Dakota entered the United States on November 2, 1889, becoming the 39th and 40th states, respectively.1 Regional differences, as well as disputes over a future capital, pushed the formation of two independent states.

Settlers continued to immigrate to North Dakota as homesteaders through the turn of the century. By 1915, 79% of North Dakota’s population were either immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants. These settlers, largely from Scandinavia, Germany, and Russia, weren’t afraid of the northern chill that prevented many Americans from moving to the region.

Presidential Elections in Early Statehood

Republicans have controlled North Dakota presidential politics for most of its history. But the state has a streak of populism that goes back to its earliest days. In 1892, the North Dakota Democratic Party and the Populist Party formed a fusion ticket and together won two of the state’s three electoral votes2. The Republican, Benjamin Harrison, won the state’s third elector.

From 1896 to 1928, though, Republicans won seven of the nine presidential contests. Democrat Woodrow Wilson then won the state’s electoral votes both in 1912 and 1916. In 1912, however, the Republican vote was split between Republican William Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, who had broken from the GOP to create his own Progressive Party. That year, Taft and Roosevelt together received about 56% of the vote while Wilson received just 34%.

Political Parties, Coalitions, and Trends in Early Statehood

These topline presidential results, however, obscure the complexity of North Dakota’s politics. The state’s early politics revolved around the concerns of farmers. Both Democrats and Republicans would absorb some of the populist reforms popular among these agrarian communities.

The populist movement had sparks of success in the 1890s but the effort got its first big win in 1906. That year, progressive Democrats and Republicans banded together to elect Democrat John Burke as governor. While he did not establish the reforms many farmers wanted, he did push for other populist policies to fight corruption, reform the voting system, and improve working conditions.

The true populist insurgency, though, would come nine years later with the formation of the Nonpartisan League. Reformers and populists who had spent years criticizing the Republican Party from within broke off to form the Nonpartisan League, or NPL, in 1915. The NPL advocated for progressive and socialist policies — most significantly government control over farming-adjacent industries (grain mills, banks, railroads) — in order to strengthen farmers and weaken urban and eastern corporations. The NPL also fought for other reforms including women’s suffrage, improved and expanded government services, and anti-interventionism. In 1916, the NPL ran a slate of candidates in the Republican Party’s primary, effectively hijacking the state-level Republican Party. By 1918, the NPL dominated statewide political offices.

Unsurprisingly, this agenda was not popular among all business leaders or out of state corporations. These interests united into the conservative Independent Voters Association. The IVA acted as a capitalist counterbalance to the socialist policies of the NPL.

By 1922, internal organizational problems, the radicalism of the group’s platform, and external attacks by the IVA had eroded the NPL’s support. The group’s ideas, though, would linger in North Dakota politics and the group itself would make a comeback in future decades.

When wartime prices for grain dropped following WWI, and again when the Great Depression hit, farmers in North Dakota suffered. Farms foreclosed, jobs were automated away, and the rural populations fell as people moved into cities. The North Dakota Farmers Union in the 1920s and a revitalized Nonpartisan League in the 1930s would emerge to once again fight low commodity prices, save farmers’ livelihoods, and push progressive reforms.

Presidential Elections Since the Midcentury

In 1932, for the first time in its history, a Democratic presidential nominee would win a majority of the vote. That year, and again in 1936, Franklin Roosevelt won decisive victories in the state.

In 1940, Midwestern native Wendell Willkie was able to win back rural, small town areas in the Northern U.S. Through these victories, he was able to bring the state back to its Republican roots even as he lost the election to Roosevelt. From that year on, with the exception of 1964, North Dakota would vote Republican in every presidential contest.

Political Parties, Coalitions, and Trends in the Midcentury

As had been the case in earlier elections, the topline presidential results don’t tell the whole story. In 1956, the Nonpartisan League merged with the Democratic Party, becoming the Democratic-NPL Party. The new party continued to fight for progressive policies including a higher minimum wage and taxes on the wealthy. While Republicans still controlled the state legislature, the new Democratic-NPL party had significant success. Before the Democratic Party and the NPL merged, Democrats held five seats in the state legislature. In 1957 that number grew to 28 and by 1959 it was 67. By the 1980s, the Democratic-NPL would be strong enough to take control of the State Senate.

Democrats also gained ground in congressional elections. In 1960, Democrats picked up a U.S. Senate seat that the party would hold through 2018. In 1980, Democrats also won the state’s at-large U.S. House seat. In 1986, Democrats won the other Senate seat, kicking off a 24-year stretch of Democratic control of the entire congressional delegation.

North Dakota’s unique brand of politics — defined by its agrarian populism — allowed Democrats to win down-ballot even as Republicans dominated presidential politics. Democrats promised to fight for North Dakota’s farmers, and in a state where agricultural concerns are paramount, this was successful. Other factors — including automatic voter registration, a tight-knit community, a willingness to vote for candidates over party, and a significant Native American population — also helped Democrats down-ballot.

A Changing Economy Changes Politics

Concentration of the farming industry has changed North Dakota politics. In 1959, there were nearly 55,000 farms averaging 755 acres in size. By 2018 there were just 26,100 farms, each averaging 1,500 acres. As giant agribusinesses began to replace small family farms, North Dakotas left-wing populist streak faded. This receding left-wing populism eroded Democratic strength in North Dakota. Also responsible for this attrition, though, is political polarization along racial, geographical, religious, and cultural lines.

The energy boom, starting in 2007, also dramatically changed the state’s economic and political landscape. With the development of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and other new technology, North Dakota’s Bakken Shale Formation opened for business. From 2006 to 2018 North Dakota increased its production of natural gas by over 1,200%. In the same period, North Dakota’s petroleum production moved from 108,000 barrels per day to 1,264,000. North Dakota now ranks 2nd among the states for total crude oil production and 10th for natural gas production.

This created lots of new jobs and a heightened demand for workers. Since 2010, North Dakota’s population has grown by about 100,000, or 13%. The oil boom, and its associated population influx, took place during the Great Recession. Amazingly, North Dakota’s unemployment rate peaked at 4.3% in 2009 while the national average was closing in on 10%.

Along with jobs, though, the oil and gas broom brought overpopulation, oil spills, unsafe working conditions, environmental concerns, and strained infrastructure. In 2016 and 2017, the Dakota Access Pipeline, and its effect on Native Americans and their ancestral lands, led to political clashes and national controversy.

The new reliance on energy production brought North Dakota even further into the Republican camp. In North Dakota, as in other energy-producing state like Wyoming and West Virginia, the Republican Party has successfully billed itself as the party of energy and Democrats as a threat to the economy and jobs. The oil boom wrung the remaining power from North Dakota Democrats.

Contemporary Politics in North Dakota

No Democratic presidential nominee has won North Dakota since Lyndon Johnson beat Barry Goldwater in 1964. Recently, though, the state has become even more staunchly Republican. In 2008, Republican nominee John McCain won North Dakota by a 9% margin. By 2016, the GOP margin had grown to 36% with Donald Trump as nominee. The message of the contemporary Republican Party is resonating strongly in The Peace Garden State.

Trump won 51 of the state’s 53 counties. He improved upon Mitt Romney’s performance in every single county in the state. The two counties Clinton did carry — Rolette and Sioux — are over 75% Native American. Together, they accounted for only about 5,000 votes, not enough to give Clinton a significant boost.

Republicans have also expanded their dominance to other federal elections. Before the 2010 midterms, Democrats held both of North Dakota’s U.S. Senate seats and its single House seat. In 2010, Republicans flipped one Senate seat and the House seat. In 2012, Heidi Heitkamp won by just 1% in an open race for the seat held by retiring Democratic Sen. Kent Conrad. But six years later, North Dakota’s Republican lean was too strong and she lost to Republican Kevin Cramer by 11%.

The Democratic-NPL Party has the best chance of winning back voters in the eastern part of the state. This is the most densely populated area and home to Fargo and Grand Forks. The state gets more rural, conservative, and Republican the farther west one goes. Even in her 2018 loss, Heitkamp was able to carry 10 eastern counties, all of which Clinton lost. The right Democratic nominee might be able to find future success in this region.

For now, though, North Dakota looks safely Republican on all political levels. In an age where geography and demographics reign supreme in politics, the white, rural state of North Dakota fits neatly into the Republican column.

1 President Benjamin Harrison shuffled the statehood papers on his desk and signed them blindly. While North Dakota is generally considered the 39th state, it is lost to history which document Harrison signed first.

2 Voters chose electors directly. There was not a slate of Democratic electors separate from the Populist ones. Two of the Populist electors were chosen. One of them cast his ballot for Cleveland, a choice that was announced beforehand.

Next Week: New York

<