The Road to 270: Maryland

By Seth Moskowitz

March 9, 2020

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Maryland

Maryland is one of the most liberal states in the country. In 2011, the state legislature passed a bill to provide in-state tuition to undocumented immigrants; a year later Marylanders voted to legalize same-sex marriage in a popular referendum. In 2012 and 2016, it gave Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton over 60% of the popular vote. It might be surprising, then, that such a liberal bastion elected a Republican, Larry Hogan, as governor in 2014 and again in 2018. Hogan, however, is a moderate on social issues while more conservative on fiscal ones. This ideological mix suits the state’s diverse, college educated, and wealthy population. To understand how Maryland became the nation’s richest state as well as one of its most diverse, we’ll go back to its pre-statehood history.

Catholic Refuge to Statehood

Europeans first settled Maryland in 1634 as a refuge for Roman Catholics, a group long discriminated against in England. The colony’s plantation-based economy originally relied on indentured and slave labor. Before the Revolutionary War, these slaves worked mostly in tobacco fields. As the industrial revolution made its way across the Atlantic, the work shifted to iron forges and wheat fields. Factory towns sprung up to process the goods and Baltimore grew as the state’s export hub.

The original charter mistakenly placed portions of Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia, within Maryland’s borders. The two states reached a settlement in 1760, with Maryland’s northern border comprising much of what would become known as the Mason-Dixon line. As one of the original 13 U.S. colonies, Maryland helped defeat the British in the Revolutionary War and joined the Union in 1788. In a final adjustment to its borders, the state ceded approximately 68 square miles of land in 1790 to help establish the capital city of Washington D.C.

Early Elections in Maryland

While most states allowed their state legislature to choose electors, Maryland split itself into districts and chose them by a popular vote within them. This is in some ways similar to the method used by Maine and Nebraska today.

In the nation’s early years, presidential elections split geographically between Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Party — popular in the northeast — and Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party — popular in the South. Maryland, with both northeastern, urban, and industrial characteristics as well as southern and agrarian ones, regularly split its Electoral College votes between the parties. In 1833, the state changed its method of choosing electors to a statewide ballot, making the vote winner-take-all. Even with this new method, Maryland remained divided and unpredictable.

As the nation’s Democratic South and Republican North began to clash, Maryland found itself in the middle. In 1856, when slavery became the dominant question in presidential elections, Maryland was the only state not to pick a clear side. Instead, Maryland cast its votes for Millard Fillmore, who had received the nomination from the Whig Party, the American Party, and the anti-immigrant American-Know-Nothing-Whig Party.

In 1860, Maryland voted for the pro-slavery Southern Democrat John Breckenridge. John Bell, the Constitutional Union Party’s candidate who ran on holding the Union together and won the other border states of Virginia and Kentucky, just barely lost to Breckenridge in Maryland.

Like other border states, Maryland allowed slavery but stayed in the Union during the Civil War. Pressure from President Lincoln, particularly after the Union victory at Fort Sumter, locked Maryland in as a pro-Union state even as secession was popular among many Marylanders reliant on the institution of slavery.

Maryland and Baltimore’s Industrial Revolution

In the years following the Civil War, Maryland would experience dramatic social change. The state’s 1864 constitution, as well as the 13th Amendment the following year, outlawed slavery. Efforts to expand the franchise brought these newly freed slaves into the electorate. The industrial revolution was also changing the character of Maryland and its largest city. Manufacturing began to take over as the state’s dominant economic force and the Baltimore Port allowed easy access to European markets. Like other northeastern cities, Baltimore drew in and prospered off of hard working and entrepreneurial immigrants. This growing population and booming economy led to the development of the state’s transportation and urban infrastructure including railroads and ports.

Post-Civil War Elections

In the elections following the Civil War, Maryland reliably voted for the Democratic nominee. Even with a constantly changing electorate, Democrats carried the state in every election from 1868 through 1892. The Democratic dominance lasted until 1896 when Democrats nominated the populist William Jennings Bryan. That year, as well as in 1900, 1904, and 1908, the plurality of Marylanders voted Republican. Even in their losses, Democrats were competitive in Maryland. The elections of 1904 and 1908 were decided by just 0.02% and 0.25%, results that ended with a split electoral delegation.

For the next 45 years — from 1912 through 1956 — Maryland’s presidential elections would flip between the parties. Democrat Woodrow Wilson would carry Maryland and the country with his isolationist stance towards entering World War I. Republicans won in the 1920s while they steered a booming economy. Democrat Franklin Roosevelt won back the state in each of his four elections from 1932-1944 on the strength of his popularity and New Deal coalition. From 1948 through 1956 Republicans would again take back Maryland — the last time they would do so outside of nationwide electoral landslides.

Economic Transformation

The two World Wars turned Maryland and Baltimore into production centers. During the first war, several military bases and sites were built in the state. This military import continued in the next war as airfields were established in Maryland and as the state became a production center for warships and aircraft.

After World War II, Maryland’s traditional economy of industrial jobs in manufacturing, coal, and railroads shifted. Returning soldiers looked to raise families, accelerating suburban growth. Baltimore’s dense downtown spread into more sprawling urban region. In the city core, demolition was more common than new growth. New infrastructure — the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel, interstates and freeways — was built to accommodate suburbanization.

Meanwhile, the nation’s agricultural capacity grew and eliminated Maryland’s primacy in the sector. As suburbanization encroached upon rural and agricultural territory, land and labor became more expensive. Small family farms and homesteads condensed into large-scale ones. Manufacturing continued its decline as well, as General Motors and Bethlehem Steel downscaled their Baltimore operations.

As the state’s manufacturing and small-scale farming industries were on the decline, others were on their way up. In the state’s southern counties rimming Washington, D.C., jobs in and around the federal government employed commuting Marylanders. In Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University and its hospital (as well as the nearby NIH and FDA) became the anchor to a growing biotech, health care, and other high information service industries. Urban renewal projects also helped transform Baltimore into a trendy city more appealing to college-educated young people. This process, while successful in drawing in the desired young transplants and tourists, also pushed out low-income longtime Baltimore residents, many of them minorities.

Demographic and Electorate Changes

During this economic transformation, Maryland turned from a state on the political margins to one heavily favoring Democrats. The state voted Democratic beginning with John F. Kennedy in 1960, only flipping back to Republicans in the three landslide years of 1972, 1984, and 1988. In 1992, Bill Clinton carried the state by 14%. Every Democratic nominee to follow would carry the state by double digits.

Maryland saw enormous economic shifts in the mid 1900s; more recent changes have been largely demographic. Black residents of Washington, D.C. moved out to the Maryland collar counties of Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties. The influx diversified the Washington D.C. and Baltimore suburbs and the new residents progressed northwards. While in 1970 Maryland’s population was 81.5% white and 17.8% black, today those numbers are 58.8% and 30.9%. Maryland also saw an influx in foreign immigration. While in 1970 people born outside of the U.S. made up just 3.2% of the state's population, by 2012 it was 14.3%. And many of these new transplants — both foreign and domestic — were highly educated. In 1990, 26.5% of Marylanders had a Bachelor’s Degree, a number that is now pushing 40%.

At the same time that minorities and college-educated whites began to sort decisively into the Democratic Party, they also began to make up a larger share of Maryland’s population. This helped flip the state to Democrats in 1992 and make it the Democratic stronghold it is today.

Recent Elections

From 1992 through 2004, the Democratic nominee consistently carried Maryland by about 15%. In 2008, Barack Obama would expand that margin to over 25%. Obama won by a similar number in 2012, even as his national margin shrunk by 3%. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the state by a 26% margin, the largest since Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 landslide.

Maryland’s transformation to one of the safest Democratic states has involved a massive leftward shift in the counties surrounding Baltimore and Washington D.C. and a rightward shift in the state’s rural regions. In 2000, Democrat Al Gore won Washington D.C.’s collar counties, Montgomery and Prince George’s, by 29% and 61% margins. In 2016, Clinton won those by 56% and 80%. Gore won Baltimore County and its neighbor Howard County by 9% and 8%. In 2016 Clinton won them by 18% and 34%. In many of the state’s more rural regions outside of the Baltimore - Washington-D.C. Metropolitan Area, Republicans gained ground. This shift, however, has not been nearly strong enough to counteract the Democrats’ dominance in the state’s dense urban corridor.

Current Political Landscape

Maryland underwent one of the most successful economic shifts in the entire nation. The state, once dominated by agriculture and manufacturing, has diversified to incorporate information and service jobs in government, education, biotech, and health care. These industries have built a strong and diverse middle class and pushed Marylanders to the top of the economic ladder. The state has the highest median household income in the nation, with the average household earning over $81,000 per year.

The economic prosperity hasn’t sheltered Maryland from political strife. The Wire, a political drama that ran from 2002-2008, documented Baltimore’s corrupted institutions — the police department, port unions, city government, public schools, and media. The state and Baltimore still have pockets of poverty that are only more vivid when contrasted with the state’s overall wealth and success. In 2015 when Freddy Gray, a young black man in Baltimore, sustained injuries that would prove fatal while being transported in a police van, Baltimore’s struggles took the national spotlight.

All this helped fell former Baltimore mayor and Maryland governor, Martin O’Malley, in his bid for the 2016 Democratic nomination. The state has other powerful elected officials including the Democratic House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer and Senator Chris Van Hollen, who served seven terms in the U.S. House before being elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016.

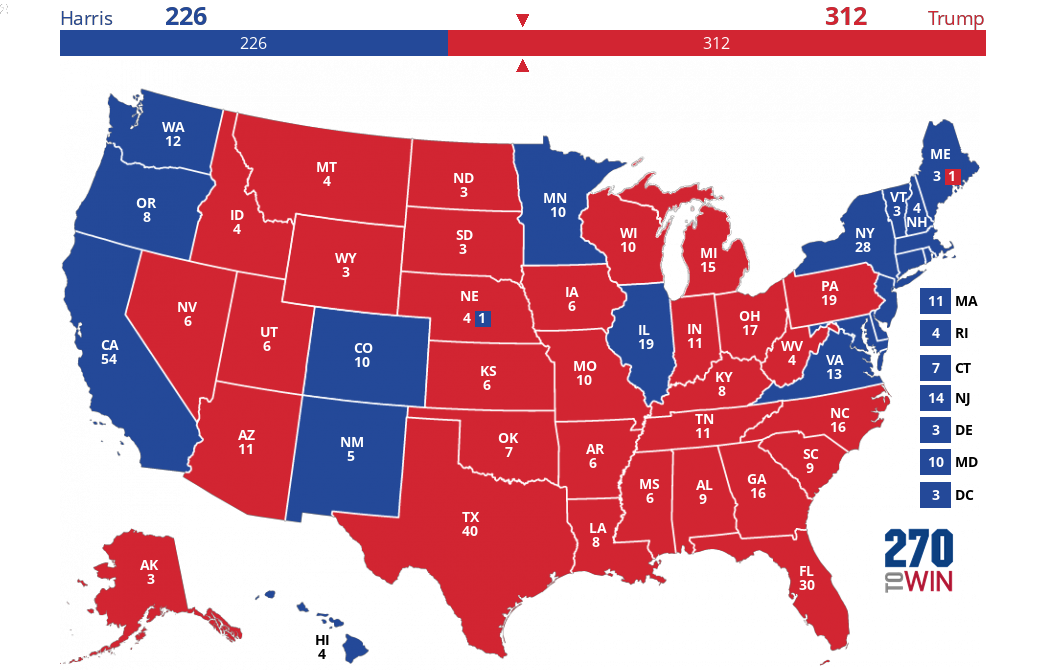

This November, neither of Maryland’s Senate seats will be on the ballot, none of the state’s U.S. House elections are expected to be competitive, and the Democratic nominee will likely carry the state by around 30%. Democrats in the state don’t have their say in the nominating process until the April 28 primary. With the field recently winnowed to two major candidates, the nominee may be a foregone conclusion by that date. Regardless of who wins the nomination and the role Maryland plays in the selection, the end result is the same. Maryland will be blue in November.

Next Week: Nebraska