The Road to 270: Nebraska

By Seth Moskowitz

March 16, 2020

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Nebraska

Nebraska is all but certain to vote for Donald Trump this November. The state, however, is one of two that awards Electoral College votes by congressional district. Nebraska’s second district is far more competitive than the state as a whole and could prove decisive in a close presidential election. As such, this week’s article will be a little different than usual. The first half will focus on Nebraska’s history and political landscape at large and the second half will zoom in to the competitive Omaha-based district.

Road to Statehood

In 1541, over 350 years before Nebraska would become a part of the United States, a Spanish explorer claimed the territory for his country. A French explorer did the same in 1682, causing land disputes that persisted until the United States bought the land from France as a part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

On their expedition to cross the country, Lewis and Clark explored the eastern and northeastern parts of the territory that border the Missouri River. A half century later, about a quarter of the Oregon Trail would lie within the future-state. In 1854, the United States established the Nebraska Territory in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a law most famous for repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing states to independently determine the legality of slavery within their borders. The new Nebraska Territory comprised parts of modern-day Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana.

After Congress squeezed Native Americans into reservations and opened the region to settlers through the Homestead Act of 1862, the population began to grow. The growth, helped along by the Union Pacific Railroad establishing its terminus and headquarters in Omaha, continued through the mid-century. In 1867, with the state's newly inflated population, Congress admitted Nebraska to the Union.

Growth and Republican Dominance

Over the next three decades, Omaha’s population would explode. Settlers continued to come for the fertile prairie land; workers immigrated to work in the meatpacking and railroad industry. Sixty miles south of Omaha, Lincoln grew around the University of Nebraska. The population grew from 29,000 in 1860 to 1,062,000 in 1890. More people moved to the state in those thirty years than would do so in the next 130.

In the 1890s, economic depression, low crop prices, and drought lowered farmers’ incomes and expectations, the latter of which had been inflated by particularly friendly agricultural conditions of the 1880s.

These economic conditions helped the populist silverite, William Jennings Bryan, rise to national prominence. The Nebraska Congressman’s 1894 speaking tour promoting the coinage of silver, a policy to raise inflation and help indebted farmers, launched him into the spotlight and his 1896 presidential run.

Bryan would run for president as a Democrat three times — in 1896, 1900, and 1908. He would carry his home state of Nebraska in the first and third runs while losing it in his second. For a state that had voted Republican since its first presidential election in 1868 — a product of the Civil War’s geographic split — voting Democratic was unusual. Nebraska would again vote for Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912 as Republicans split their vote between Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft. Wilson would also win the state in 1916, a reward for keeping the U.S. out of World War I.

From there, Nebraska’s presidential electoral history is simple: no Democrat would win statewide outside of the massive landslides in 1932, 1936, and 1964. After 1964, every Republican nominee would carry the state by double digits.

While the state suffered during the Great Depression, it was not friendly to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Nebraskans opposed what they saw as government overreach and opposed Roosevelt in his 1940 and 1944 reelection bids.

A Changing Economy and Recent Elections

During and after World War II, Nebraska’s economy changed. In 1940, the Army constructed an aircraft plant near Omaha, a decision that built the region’s manufacturing capacity and workforce. After the war, the plant was renamed Offutt Air Force Base and become the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command.

As agriculture became less lucrative and farmers fell into debt, Nebraska’s family farms began to condense. Factory farms expanded their acreage while farmers moved from their rural homesteads into the state’s suburban and urban areas. In the late 1980s, the economy — helped along with government tax incentives — shifted towards manufacturing and oil refining. A number of large companies — Berkshire Hathaway, Kiewit, Tenaska — built and expanded headquarters in Omaha. An ecosystem of smaller financial, telecommunications, and insurance companies built up around these established companies and the University of Nebraska helped churn out a qualified workforce.

Even with this new economy, Omaha and Nebraska still relied on their historical economic pillars — agriculture and meatpacking. These traditional industries drew in workers, many of them black and Hispanic, growing and diversifying the state’s population. Omaha in particular became a home for young transplants looking for jobs and a low cost of living.

The state as a whole, however, is still 88% white and votes accordingly. Nebraska has long been far to the right of the nation, and that trend continued into the 21st Century. George W. Bush carried the state by 29% and 33% in 2000 and 2004. John McCain won by a less impressive, but still safe, 15%, in 2008. Mitt Romney expanded the margin to 22% in 2012. Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton by 25%, a 59% to 34% victory. Trump carried all but two counties — Douglas (Omaha) and Lancaster (Lincoln) — in his 2016 rout.

Nebraska’s Second Congressional District

Nebraska, however, is one of two states that divides its Electoral College votes by congressional district. The state awards one electoral vote to the popular vote winner within each district and two to the statewide popular vote winner.

Nebraska has used this formula since 1992. Barack Obama is the only presidential candidate to successfully isolate one of the state’s electoral votes since it adopted the Congressional District Method. In fact, this is the only electoral vote any Democrat has received from Nebraska since Lyndon Johnson carried the state in his 1964 blowout. In 2008, Barack Obama won the state’s second congressional district 49.8% to John McCain’s 48.6% (a margin of just 3,400 votes) even as he lost the statewide popular vote and the other two congressional districts.

At the time, the second district included all of Douglas County (Omaha) and the eastern portions of its southern neighbor, Sarpy County. Sarpy’s eastern third includes the Offutt Airforce Base and Bellevue, a region friendlier to Democrats than Sarpy’s rural western parts. After the 2010 Census, Nebraska’s ostensibly nonpartisan legislature redrew the second district’s lines to include Sarpy’s more Republican west while removing the more Democratic east. The redraw only slightly shifted the district’s partisan balance at the time and Mitt Romney would have carried it in 2012 regardless. Under the new lines, Romney beat Obama in NE-02 by 7.1%.

In 2016, as suburban and college educated white voters swung away from Donald Trump, the second district came back into contention. Hillary Clinton stopped in the district for a campaign rally with Warren Buffett and her campaign aired ads, but it was not enough. Donald Trump carried the district 48.2% to Hillary Clinton’s 46% — a 2.2% and 6,400 vote margin. Clinton carried Douglas County by 2% but Trump overwhelmed her with a 24% margin in the portion of the district that lies in in Sarpy County.

The district is 82% white, 9% black, and 6% Hispanic, a racial breakdown that is similar, but about 5% more black, than the state as a whole. The second district’s white population, however, is more educated than the state’s overall white population. Thirty-three percent of white people in the state have Bachelor’s Degrees compared to 44% of white voters in the second district. Among white voters, those with college degrees are far more Democratic. The second district’s higher portion of college-educated white and black voters make it more friendly to Democrats than the whiter, less educated population of Nebraska overall.

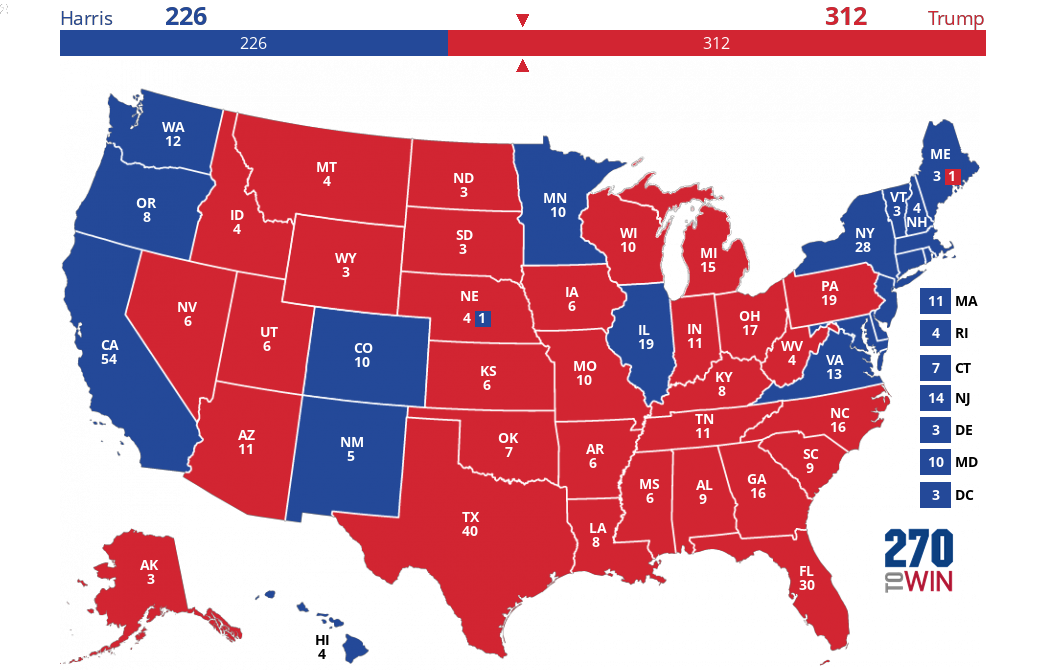

In a particularly close election, the second district could decide the Electoral College. If the Democratic nominee were to flip Michigan, Wisconsin, and Arizona, while leaving the rest of the map identical to 2016, the nominees would be tied at 269 electoral votes. If the Democrat were able to flip NE-02, it would push them to a 270-268 victory. This is just one of several plausible scenarios in which Nebraska’s lone electoral vote could be the tie-making or tie-breaking electoral vote.

As the parties’ coalitions shift and suburban and college-educated white voters move to the Democratic Party, NE-02 looks increasingly like a district Democrats should be able to flip. If Donald Trump is able to again squeak out a victory here, he will be leaning heavily on Sarpy County while hoping not to get smothered in Douglas.

For now, Nebraska’s second district is a Toss-Up. The system for awarding electoral votes here will draw outsize attention to a state that is almost certain to go to Donald Trump by 20 to 30%. November’s presidential contest may well be decided by three Rust Belt states, three Sun Belt states, and a small congressional district in the heart of the country: Nebraska’s Second.

Next Week: Kansas